Always pressed to retire, Steven Soderbergh has made some of his best-ever work by constantly innovating with form and finding new ways of transcending the “digital boundaries” of filmmaking. Whether shooting on iPhones or creating wholly unique camera angles, Soderbergh is always at the forefront of true formal innovation that feels rare in the moviegoing era we live in today. It is, however, a bit funny that the director has frequently retired in his career and returns a few years later, as if he has “one more left” in him. In 2017, Logan Lucky was his grand return to this true post-digital era Soderbergh has been in, and we’ve since gotten seven films under his belt, of varying quality, but with an always precise sense of style.

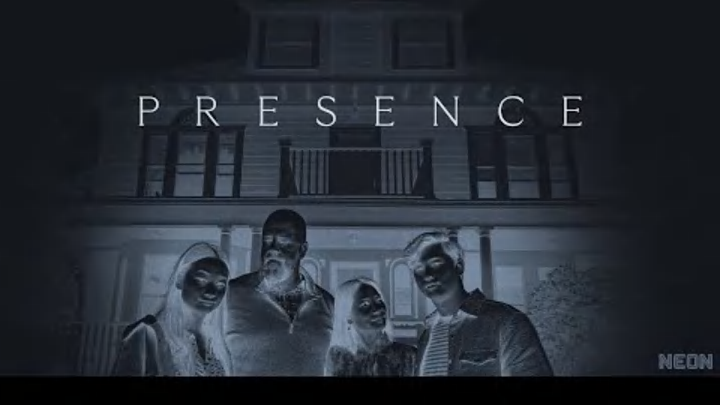

Not all of his post-Logan Lucky efforts were masterpieces (looking at you, The Laundromat), but they each have a consistent stylistic quality to them that's decidedly Soderbergh. Even when using iPhones in an attempt to break free of the limitations digital photography offers (notably on ARRI ALEXA 65s and the like), Soderbergh creates a singular artistic imprint that’s entirely recognizable from picture-to-picture, always in service of the story he wants to tell. However, with his latest venture, Presence, which releases this January, the household style he’s mostly known for is completely gone in favor of a story told through the perspective of a disembodied spirit, who careens a house where a new family is moving into.

At first, the daughter, Chloe (Callina Liang) believes it to be the ghost of her best friend, Nadia, who died of a drug overdose not long ago. She has been grappling with this loss ever since, and has distanced herself from the rest of her family, which is comprised of mother Rebecca (Lucy Liu), father Chris (Chris Sullivan), and brother Tyler (Eddy Maday). At first, the ghost only observes the family without intervention. Soderbergh, who also acts as cinematographer (through his pseudonym “Peter Andrews”), acclimates us to this unique perspective, one whose quasi-fish-eyed point of view continuously floats in the air and glides from one room to the next, never knowing where his camera will end up by the time the scene begins and ends.

The perspective of a ghost

One element that could’ve enhanced the feeling that we’re observing the family through a spirit would be if that invisible character moved through walls, but Soderbergh refuses to play in any classic ‘ghost story’ trope that could perhaps dilute the rock-solid emotional drama at the core of Presence. That said, he can’t escape them when the spirit begins to intervene, first by signaling to Chloe its “presence” (hence, the title), then by actively attempting to stop her from getting into harm’s way when it sees things she is ignoring. Afterwards, it breaks the “bond” it had with Chloe, and makes itself known to the family.

This leads into Presence’s most rudimentary scenes, in which the house’s realtor, Cece (Julia Fox), brings over a spirit medium to communicate with whoever inhabits the home. Those scenes, while visually and aurally enrapturing, are sadly not as intriguing as the family drama at the core of the movie’s narrative. It may be due to its lean runtime of 85 minutes, but even then, Presence fully fleshes out what’s important.

As discombobulating as the stylistic approach may be in the movie’s opening sections, it doesn’t take long for us to start getting acclimated into how Soderbergh structures his picture, with sharp cuts to black at pivotal moments representing a transition from scene-to-scene and camera movements that feel as if we are the spirit floating around the house, with our soul lingering between life and death, without any recollection to who we were, and what we should now do with our newfound abilities.

His camera becomes more than a simple “observer,” and turns into the beating heart and soul of why Presence works so well. When Chloe has difficulty overcoming the monumental loss of her best friend, the mere apparition of an otherworldly being inside the house acts as form of catharsis in accepting our ultimate fate as a temporary bridge between the real and spirit worlds. In trying to communicate with “Nadia” (or someone else), Chloe is also trying to better understand herself while her family refuses to entertain what she’s experiencing, until the “presence” makes it clear that it’s existing within the environment.

A fractured family drama at the heart of Presence

Like most of his movies, Soderbergh has no desire to handhold the audience, after doing so in Ocean’s Eleven and never again. He instead presents fragments of a fractured family that refuses to talk to one another and are always in their own internal bubbles. This creates a sense of tension inside the house that only intensifies as they must come together to find a solution in getting rid of a spirit that apparently refuses to leave. When Tyler scolds Chloe for still grieving the loss of her best friend, or when Chris has no idea what to do anymore, knowing that his wife is in deep legal trouble, how can they ever repair the (internal and external) wounds that has divided them long ago?

Soderbergh rightfully doesn’t have the answers to this central question, and it’s what makes Presence such an engrossing and immersive piece of work. Most of it is left to interpretation, even the final scene, which hits like a total punch to the gut as we realize who this spirit was all along. Lucy Liu, in the best performance she’s given in ages and a worthy showcase of her dramatic talents, fills this sequence with so much sorrow that it becomes hard for the audience to hope that this family will ever heal, even long after the events of the movie have transpired.

Throughout Presence, the guiding thematic underpinning that links Soderbergh’s fragmented one-takes is the instillation of hope within Chloe that this world can get better when accepting the inextricable fact that there is life beyond death, no matter what shape it takes. Nihilists may argue to the contrary, but Soderbergh is an optimist. He wants to believe in our capacity to live forever, in whatever awaits us after we move on from this Earth. Chloe doesn’t believe this at first, but upon contacting and further understanding the spirit that continuously interacts with her, perhaps the life she currently has could get better if she has the willingness to accept her fate.

On the flip side, Chris’ growing anxieties worsen as the spirit appears, and amplify what he has been feeling for a long time. In representing this sense of professional and personal alienation, Sullivan also impresses in giving the right emotional texture to a figure we can’t fully read (even less than the ghost), who seems further distanced from his family than the spirit itself. It could be an even greater turn than his most well-known role in This is Us, particularly in how his character’s already pressing state is further upended by an entity he does not want to understand, nor even perceive at the same level as his daughter.

Soderbergh at his most polarizing in years

The family story at the heart of Presence is why audiences are compelled to keep watching, especially in how minute Soderbergh is in enveloping us through the “eyes” of a ghost who constantly moves up and down the house as if it is also inadvertently part of the family. It’s only when the movie reaches an unearned, and half-baked final “twist” that Soderbergh loses the aesthetic and thematic grip he had on the audience for pure shock value. It registers the drama as unimportant, which feels like a cardinal mistake with what the director has been painstakingly developing before such a denouement.

This conclusion may be Soderbergh at his most polarizing since Ocean’s Twelve, and it certainly will make or break the enjoyment of many audience members who were at first enamored by such a personal reinvention of his stylistic conventions. However, he doesn’t let us off the hook this easy, with a final scene so good one could retroactively ignore the “twist” that might have tarnished the whole thing, were it not for Lucy Liu pouring all of her emotions in front of us. It’s a genuine tour-de-force that will stay with you long after the credits have finished rolling and you’ve come back home, still ruminating about what it all means.

Maybe you won’t figure it out, but none of us truly know what comes after life. It could be nothing. It probably is. But it could also open the door to something else entirely. We won’t know the greatest mystery until it’s time, and, no matter how some of us aren’t afraid or ready to face the idea of dying, the fear of the unknown is real, and it is coming for us all. However, the hope that we can regrow after death may keep us alive, physically and spiritually, far longer than we think…

Presence releases in theatres on January 24.